commit

250823c88a

3 changed files with 0 additions and 536 deletions

Binary file not shown.

|

|

@ -1,292 +0,0 @@

|

|||

# A Case for a Pythonic Python GUI

|

||||

|

||||

Straightforward, compact, intuitive, minimalistic, and, of course, fun!

|

||||

|

||||

These are a few of the adjectives I hear from people when they describe what excites them about Python. Often you can research and complete a project in a single day using Python. It does short and long term code equally well too. The code-build-run cycle time can be as short as you want to make it, perhaps single-digit seconds. Python is the perfect "impatient programmer's language".

|

||||

|

||||

There are many built-in packages in the standard library and PyPI reports 10,000s more that you can install with a single line of text using the pip command.

|

||||

|

||||

There have been a lot of GUI packages over the years with the official python GUI package being tkinter.

|

||||

|

||||

When it comes to GUIs, there is not currently a GUI framework available that beginners and advanced programmers alike can use to make a full-featured attractive, custom, GUI quickly. Nor, in this author's opinion, are the well-known full-featured GUI pacakages particularly "Straightforward, compact, intuitive, minimalistic, and, of course, fun". "Full featured" here means having control over the placement of individual widgets with the widget list being all of the usual widgets, label, entry, sliders, drop down menus, menu bars, etc.

|

||||

|

||||

If nothing existed and you could define your own GUI framework to fill this missing framework, what would be some of the characteristics for a Python GUI interface?

|

||||

|

||||

If there is/was, it's ones of the best well-kept secrets about Python as student and beginners post on the Internet seeking help in finding a Python GUI framework that they have a prayer of being able to use. In the r/Python subreddit, the question "What GUI Framework Should I Choose" is asked approx every 3 days. Certainly at least once a week and at times it's every day or every other day.

|

||||

|

||||

A large population of Python developers, data scientists, makers, and hobbiests are being left out of the Python GUI tent. Users, and developers are users too, are beyond text input and output. That ship sailed with Windows 3.1 in the 90's. Human beings enjoy using the computer with a mouse, and a GUI.

|

||||

|

||||

This article describes one way to enable everyone that wants to add a GUI to their program to be successful

|

||||

|

||||

## Definitions, generalities & boundaries

|

||||

|

||||

This is a subjective view and you might disagree. But it's one based on facts. It's a fact that at the moment someone with 1 week's experience will be unable to create a GUI using tkinter, Qt, Flask, WxPython, etc. If these sorts of articles upset you, this would be an excellent time for you to surf off to some other bright shiney thing.

|

||||

|

||||

This article includes observations, conclusions, and recommendations that are not meant to cover or represent 100% of the possible situations. In terms of GUIs, the benchmark set is 80% of the use cases.

|

||||

|

||||

Corner cases exist in all areas of problems. There are "yea but what about...." questions you can ask about anything and everything in the universe. There's no attempt being made nor claimed that this proposal solves every GUI prohblem, every programmer's educational level, every runtime environment, etc.

|

||||

|

||||

There is also the question of how "modern", "beautiful" or "attractive" your GUI will be. Much of the attractiveness is in the hands of the user. 20% of the use cases includes fancy interfaces that perhaps a commercial product or a website desires. Animating a button isn't (yet) part of the discussion.

|

||||

|

||||

This architecture is targeted at user code, not library code. In other words, the person writing the code and using the code is a "user", not a person writing a library module.

|

||||

|

||||

To be a "GUI" in this discussion:

|

||||

* A library needs to provide access to all of the well-known GUI widgets (Text, Buttons, Sliders, etc)

|

||||

* Allows the user to place Widgets in any arrangement desired by the user

|

||||

(i.e. they are not dumbed down nor are they templates you choose from)

|

||||

* The primary use is User Interface to a Python application (as opposed to serving up web pages)

|

||||

|

||||

### Pythonic

|

||||

|

||||

Now there's a loaded word. It's subjective to be sure, but there certain traits, patterns or pieces of code that make them more or less Pythonic "feeling".

|

||||

|

||||

A few traits that I find particularly enjoyable about the language are:

|

||||

* User code is often short.

|

||||

* Code can be simultaneusly compact and readable.

|

||||

* Python emphasises simplicity.

|

||||

* It's modular and has namespaces

|

||||

* List and Dictionary containers are hecka-powerful (this was surprising)

|

||||

|

||||

Perhaps not part of the normal definition, but a trait just as important:

|

||||

* It's within the reach of a beginner

|

||||

|

||||

*Few things are truly out of reach of the beginner in Python.*

|

||||

|

||||

Look at Threads for example. After reading the 2 pages on Threads from the Python documentation, someone within the first couple of months of starting their Python education can figure out how to create and start a thread.

|

||||

|

||||

Here is what a beginner needs to do in order to run their first thread in Python

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

import threading

|

||||

|

||||

my_thread = threading.Thread(target=my_thread_func)

|

||||

my_thread.start()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

It seems like this is often the case in Python, a couple of lines is all you need to get a lot accomplished.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## The Python GUI Libraries

|

||||

|

||||

There are a lot of choices for GUI libraries in Python. Based on posts I have seen over the past year in the Reddit r/LearnPython and r/Python, I believe these three packages are among the most recommended by users to posters asking for help. Maybe they're not the most downloaded, or installed, but they're all ***mentioned*** heavily. The recommendations needed to boil down to something, and this is the list of what I think are three of the more popular packages being suggested when someone asks about building a *desktop GUI* for their Python program.

|

||||

|

||||

* tkinter - the defacto standard

|

||||

* Qt (in its many forms) - the 800 pound gorilla

|

||||

* WxPython - a nice, slightly smaller gorilla

|

||||

|

||||

Let's call them "the 3 GUI packages" for reference purposes. They may not statistically BE the top 3, but some label is needed for this group and that's the label they're getting here.

|

||||

|

||||

Then there are the Python GUI libraries written in Python for Python. These are among my favorites

|

||||

|

||||

* Kivy - The only desktop GUI in this list written in Python for Python. Also happens to run on mobile devices

|

||||

* Remi - A web GUI that's tiny (100k) and runs everywhere including Raspberry Pi's

|

||||

* PySimpleGUI - A unified GUI SDK that offers a single set of calls that can hook to multiple "renderers"

|

||||

|

||||

What's not in this list are any of the Web GUIs (Remi being the exception)

|

||||

|

||||

There are plenty others, but for this discussion, this is our list. Disagree if you want, but ahead is the direction we're going now.

|

||||

|

||||

## The 3 GUI Packages

|

||||

|

||||

### Not From Here

|

||||

|

||||

One interesting and problematic fact about the 3 GUI pacakges listed in Python is that they were not written *for* Python. They were designed and used with C++ prior to being brought over to Python. Or as is the case with tkinter, used with TCL, a scripting language. Bringing an existing GUI library into Python isn't the problem when it comes to reaching more potential Python GUI users.

|

||||

|

||||

The problem is that they also brought a rigid definition of how a user's GUI code is be architected. You will have these classes in your code. You will need to have a certain amount of experience/education to make something of substance.

|

||||

|

||||

### The Object Oriented GUI

|

||||

|

||||

Classes are a way to create new types in Python. They are also used, heavily, in Object Oriented designs / architectures.

|

||||

|

||||

The "preferred" (only practical) way to use these GUI packages require the end user to design and write their GUI in an object oriented manner. Pick up a book on any of these GUI libraries and you'll see in the exercises is the word Class. It's just how it is.

|

||||

|

||||

Sure, you can, with some effort, "get around" using classes, but it's not straightforward nor easy, a couple of the defining characteristics of being "pythonic". You shouldn't have to do this to begin with.

|

||||

|

||||

Think through the Python standard library and it's many packages. Do any of these packages require you to design large sections of your code in a particular way in order to use them?

|

||||

|

||||

### Programming For Events

|

||||

|

||||

Some programming languages, like C#, utilize events and callbacks heavily. Some designs also utilize callbacks. The 3 GUI packages all handle events by calling a user's callback function.

|

||||

|

||||

When a button is pressed in tkinter, for example, the function specified when the user created the button is called. All of the 3 GUIs work this way, calling a user's function when an event happens.

|

||||

|

||||

Callbacks are normal for some languages, but Python isn't one of them when it comes to the way the standard library is concerned.

|

||||

|

||||

In Python, if you want something called, you call it, generally speaking.

|

||||

|

||||

### Example - Events in Python - Queues

|

||||

|

||||

Let's take queues as an example for handling "events". In the Python library there is a `queue` module that has an object called, you guessed it, `Queue`. In some languages or libraries, a Queue object like this one would generate a callback when something arrives in the queue.

|

||||

|

||||

The way this `Queue` works in Python is that you `get` an item from the Queue. There are 2 modes you can use, blocking and non-blocking. Additionally, if blocking is specified, you can set a timeout value that will raise an Empty Exception when nothing is found in the queue within the timeout.

|

||||

|

||||

To create a queue and put something in it:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

my_queue = queue.Queue()

|

||||

my_queue.put('hello')

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Then later to read the queue:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

item = my_queue.get() # blocks by default

|

||||

print(item)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This above code will print "hello"

|

||||

|

||||

If you wanted to call a function when something arrives in your queue, you would simply add a function call to your code after you read the queue.

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

item = my_queue.get() # blocks by default

|

||||

print(item)

|

||||

my_function(item) # calling a function as if it were a "callback function"

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

\* Remember this "get" model for accessing data, you'll be seeing it again later.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## A Proposed GUI Model for Python

|

||||

|

||||

When thinking about making a GUI module in Python, from scratch, what would be some of the defining characteristics? Here's my short list:

|

||||

|

||||

* Be accessable to everyone

|

||||

* Make it "Pythonic", of course

|

||||

* Make use of the Python language's unique constructs

|

||||

|

||||

### PySimpleGUI's Attempt at a GUI Model

|

||||

|

||||

The remainder of this article will be utilizing the PySimpleGUI package's APIs and objects as a concrete way to describe the point to be made, that Python GUIs can be more Pythonic than they are today.

|

||||

|

||||

PySimpleGUI has made an attempt at creating a logical, Pythonic model for creating and using GUIs in Python.

|

||||

|

||||

If you're reading this, you've likely already read about or experienced the concepts and characteristics of the 3 packages already discussed so no need to fill up the page with examples from the 3 packages. If you want to learn more about them, a Google search will turn up plenty for you to study.

|

||||

|

||||

Let's talk about the proposed GUI model's characteristics individually

|

||||

|

||||

#### Be Accessable to Everyone

|

||||

|

||||

Since everything's an object in Python and Python programmers are confortable using objects, use objects in a way that's logical and simple, but *don't require the user to create new object definitions of their own* (i.e. they don't have to write the word class).

|

||||

|

||||

In order to make a button, users *use* the `Button` object. To show some text in the window it's a `Text` object, etc. We're just talking about using these objects, just like Theads or Queues.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Python's Core Types

|

||||

|

||||

Python's `List` and `Dictionary` types are fundamental to say the least. When first hearing about Python and its `Lists` I honestly didn't understand what the excitement was all about. I couldn't envision that a list of stuff could make a language powerful (and popular too).

|

||||

|

||||

#### Defining a Window's "Layout"

|

||||

|

||||

How about we define our window using nothing but lists? Everyone that programs Python knows what a list is, how to make on, and how to operate on them too. Our window's "layout" is a "list of lists". What is meant by that is that 1 "row" of a window's widgets is a list.

|

||||

|

||||

Let's use the 2 objects mentioned already, Text and Button, to make a window.

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

layout = [ [Text('This is some text on the first row')],

|

||||

[Text('And text on second row'), Button('Our Button')] ]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

What we have is a list, with 2 lists inside of it. Each of the interrior lists represents 1 row of the GUI. Looking at this layout, It's probably obvious what this window will look like.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Making a Window

|

||||

|

||||

We've got our window's interrior, now let's make a window. Like other std lib calls, such as Threads, mentioned before, it's a simple object that users interact with.

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

window = Window('Title of window', layout)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Here we have defined a window, put a title on it, and we passed the layout it's supposed to have inside of it.

|

||||

|

||||

Our next step will be display the window and deal with what we want our button to do. Notice that unlike the 3 GUI frameworks, our `Button` object doesn't have a callback function. How are we supposed to know when someone clicks the button?

|

||||

|

||||

#### "Reading" a Window

|

||||

|

||||

The way we're going to get the events is using the exact same technique that our Queue example earlier did. For the queue, the call get `get`. For PySimpleGUI Windows, the call is `read`. Let's add that to our program and we'll be done.

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

from PySimpleGUI import Window, Text, Button

|

||||

|

||||

layout = [ [Text('This is some text on the first row')],

|

||||

[Text('And text on second row'), Button('Our Button')] ]

|

||||

|

||||

window = Window('Title of window', layout) # make the window

|

||||

stuff = window.read()

|

||||

print(stuff) # let's print the stuff that's returned

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Here's what happens when we run this program

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

When the button is clicked, the variable `stuff` is printed. It has the value:

|

||||

```

|

||||

('Our Button', {})

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

It looks like what's being returned is a tuple. The first part is our button's text, called "the event" in PySimpleGUI, the second part is an empty dictionary. If there were input fields in this window, then the dictionary would contains the values of those fields.

|

||||

|

||||

Normally the `read` call is written this way in PySimpleGUI so that the tuple is assigned to 2 variables:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

event, values = window.read()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This unpacks the 2 values in to 2 variables `event` representing the event that caused the `read` to return. The `values` variable contains all of the values in the input fields for the window.

|

||||

|

||||

#### `Window.read()` is Like `Queue.get()`

|

||||

|

||||

\* Recall earlier in the Queue example I said the `Queue.get` model would be seen again. You just saw it in the `window.read()` call. The default action is to block on the `read`. Just like `Queue.get()` you can put a timeout value on the call so that the call is not blocking. Instead of completely blocking the block will end after the timeout and return back to you, a "block with a timeout".

|

||||

|

||||

Here is how you can get a window's events in the same "block with a timeout" way. In this example, the `timeout` of 100 means "block for up to 100 ms" for an event to take place, then return.

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

event, values = window.read(timeout=100)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

#### Callbacks

|

||||

|

||||

If you want a function to be called when a button is pressed in your window, then you quite simply see if the event you received is that button and then YOU make the call.

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

event, values = window.read()

|

||||

|

||||

if event == 'My Button': # if the button was clicked then

|

||||

my_callback('My Button', values, ....) # make your callback

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Experience has shown, however, that these "callbacks" are not used by most people. Often times the event is handled right on the spot, especially if the action to take is short.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## The Fun Begins - Applying Python's Capabilities with GUIs

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Since we're storing our window's GUI layout in a Python list, that means we can do fun Pythony things to create these layouts. One such activity is utilizing List Comprehensions to generate a layout.

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

from PySimpleGUI import Text, CBox, Input, Button, Window

|

||||

|

||||

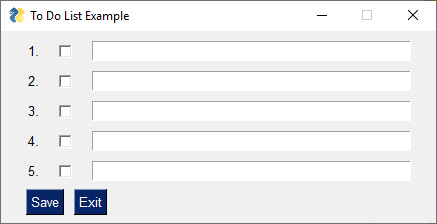

layout = [[Text(f'{i}. '), CBox(''), Input()] for i in range(1,6)] + \

|

||||

[[Button('Save'), Button('Exit')]]

|

||||

|

||||

window = Window('To Do List Example', layout)

|

||||

event, values = window.read()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

In addition to building the of items using the List Comprehension, we were able to simply "tack on" the two buttons at the bottom of the window.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## Summary

|

||||

|

||||

If this non-OOP GUI architecture is appealing to you then give PySimpleGUI a try. PySimpleGUI is relatively new, released in July 2018 and will currently "render" your GUI window **using** any of the 3 GUI packages as the backend as well as being able to show your window in your browser by using Remi as the backend.

|

||||

|

||||

The super-simple examples shown in this article are just that, super-simple examples. The "Simple" of PySimpleGUI does not describe the problem space, but rather the difficultly in solving your GUI problems.

|

||||

|

||||

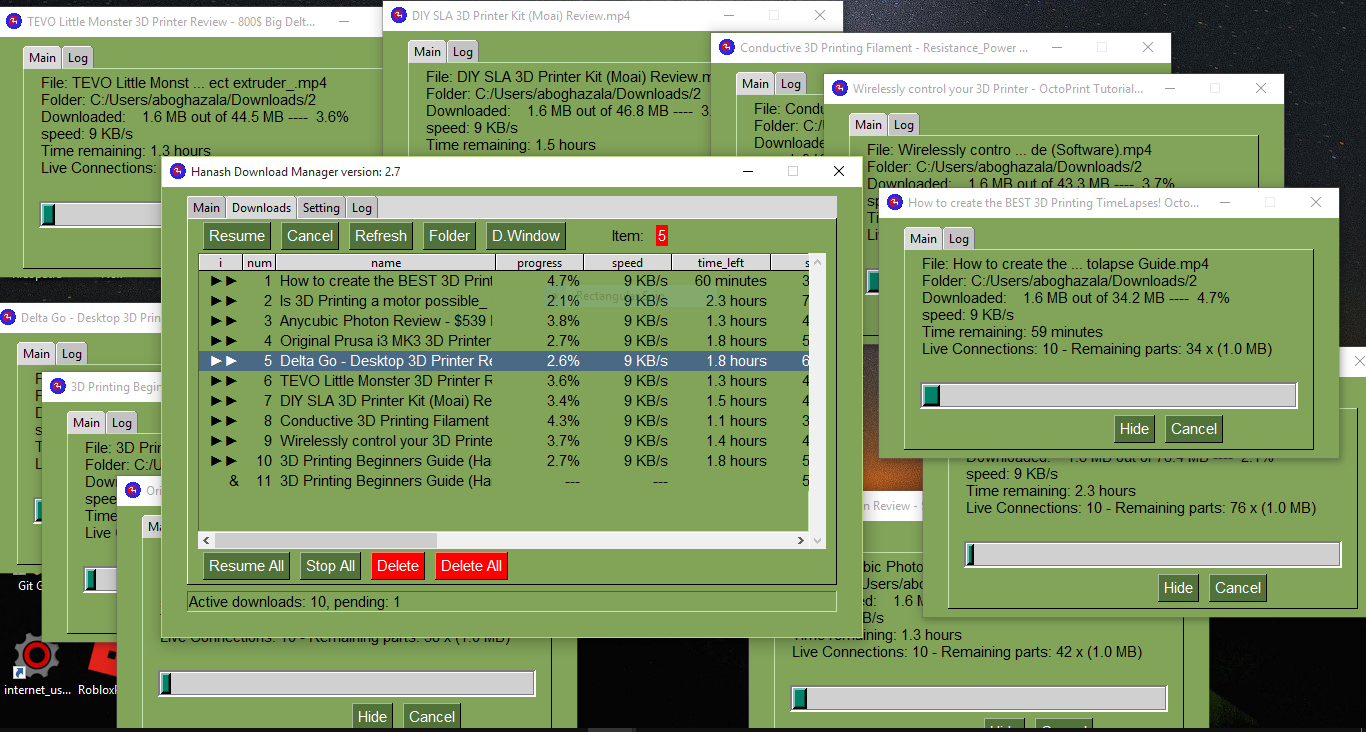

Most people would not describe this PySimpleGUI creation as "simple".

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

You can learn more about PySimpleGUI by visiting [PySimpleGUI.org](http://www.PySimpleGUI.org).

|

||||

|

|

@ -1,244 +0,0 @@

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

# PySimpleGUI Architecture

|

||||

|

||||

29-Nov-2018

|

||||

|

||||

PySimpleGUI is a "wrapper" for tkinter and Qt, with more on the way. Their are a number of "tricks" / architecture decisions that make this package appealing to both beginners and experienced GUI developers. Both will appreciate the simplicity. Simple doesn't mean shallow. There is considerable depth to the PySimpleGUI architecture.

|

||||

|

||||

# What is it?

|

||||

|

||||

PySimpleGUI is a code-generator in many ways. When you get and configure a "Text Element (Widget)", PySimpleGUI makes ***exactly*** the same tkinter or Qt calls that a developer would.

|

||||

|

||||

Here is part of the code that is executed when you create a Text Widget.

|

||||

```python

|

||||

element.QT_Label = qlabel = QLabel(element.DisplayText, toplevel_win.QTWindow)

|

||||

if element.Justification is not None:

|

||||

justification = element.Justification

|

||||

elif toplevel_win.TextJustification is not None:

|

||||

justification = toplevel_win.TextJustification

|

||||

else:

|

||||

justification = DEFAULT_TEXT_JUSTIFICATION

|

||||

if justification[0] == 'c':

|

||||

element.QT_Label.setAlignment(Qt.AlignCenter)

|

||||

elif justification[0] == 'r':

|

||||

element.QT_Label.setAlignment(Qt.AlignRight)

|

||||

if not auto_size_text:

|

||||

if element_size[0] is not None:

|

||||

element.QT_Label.setFixedWidth(element_size[0])

|

||||

if element_size[1] is not None:

|

||||

element.QT_Label.setFixedHeight(element_size[1])

|

||||

```

|

||||

The "beauty" or PySimpleGUI is the code you see above was specified with this line of code

|

||||

|

||||

`Text('Text', justification='left', size=(20,1))`

|

||||

|

||||

You can see just how little effort it took to generate, and configure on your behalf, code that resembles hand-generated Qt code.

|

||||

|

||||

## Architectural Decisions / Direction / Goals

|

||||

* Present a GUI interface that is not object oriented

|

||||

* Run an event loop within the user's application

|

||||

* Events (button clicks, keystrokes, menu choices, etc) are funneled through a single interface, Window.Read()

|

||||

* Users can use simple 'if' statements to act upon the GUIs events.... if this button press, do this.

|

||||

* There are no callbacks

|

||||

* Can change a widget's settings is a single call

|

||||

* Widget interaction is modeled simply, through simple widget updates

|

||||

* Change Widget A's value to value of Widget B is a single call

|

||||

* A widget's current value is returned in a dictionary when there is an event

|

||||

* Can duplicate nearly any window layout created by coding directly in tkinter/Qt.

|

||||

* Create complete documentation with a LOT of illustrations

|

||||

* Don't try to solve all GUI problems.

|

||||

* Be the 80% of 80/20. Leave the difficult 20% to the major frameworks. The the other 80% of GUI problems.

|

||||

|

||||

This is the magic combination that is PySimpleGUI. It's a unique design that is approachable and enjoyable to use.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

# Window Definition

|

||||

|

||||

## Widgets (Elements in PySimpleGUI-speak)

|

||||

|

||||

Creating widgets and placing them into a window definition is done with a single object, named appropriately in a simple manner. There are no "Label" widgets, but there is a "Text" one.

|

||||

|

||||

PySimpleGUI takes advantage of the Python named parameter feature. Object calls and methods are loaded up with lots of potential parameters. An IDE is a must. Let's look at a Text widget.

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

Text(text, size=(None, None), auto_size_text=None, click_submits=None, relief=None, font=None, text_color=None, background_color=None, justification=None, pad=None, margins=None, key=None, tooltip=None)

|

||||

```

|

||||

There are 13 different values and settings that can be specified when creating a Text widget. They are set when you create the widget, not several lines away.

|

||||

|

||||

The amount of code required to set those 13 values is certainly greater than 1 line of code per value. Closer to 2 or 3.

|

||||

|

||||

Not only are you setting the visible settings for a Text widget, but you're setting some behaviors. For example, `enable_events` will cause this Text widget to inform the application when someone clicks on the text. In 1 parameter we've done the work of several lines of code dealing with callbacks. Callbacks are not something PySimpleGUI have to deal with. There are no callbacks.

|

||||

|

||||

## Defining a Window

|

||||

|

||||

Break a window can be broken down into rows like this:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Then stack row "rows"up and you've got yourself a window.

|

||||

|

||||

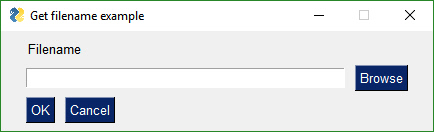

If you were to break down the sketched out window into Widgets, you would get something like this:

|

||||

"Filename"

|

||||

Input Text, Browse for files

|

||||

Ok button, Cancel button

|

||||

|

||||

To create PySimpleGUI from this, you simply make a list for each row and put those lists together.

|

||||

|

||||

## Example Code - Simple Form-style Window

|

||||

```python

|

||||

import PySimpleGUI as sg

|

||||

|

||||

layout = [[sg.Text('Filename')],

|

||||

[sg.Input(), sg.FileBrowse()],

|

||||

[sg.OK(), sg.Cancel()] ]

|

||||

|

||||

event, values = sg.Window('Get filename example').Layout(layout).Read()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Here is a complete program that will show the example window, get the values from the user.

|

||||

|

||||

That's all you need. It's "simple" after all.

|

||||

|

||||

Your `layout` is a visual representation of your window. You can clearly see 3 rows of widgets being defined. If you would like your text to be red, then your layout would look like this:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

layout = [[sg.Text('Filename', text_color='red')],

|

||||

[sg.Input(), sg.FileBrowse()],

|

||||

[sg.OK(), sg.Cancel()]]

|

||||

```

|

||||

# Event Loops

|

||||

|

||||

## Example Code - Window with Event Loop

|

||||

|

||||

The event loop in PySimpleGUI is where all the action takes place. There are no callbacks in PySimpleGUI. All of the code is located in 1 place, inside the loop.

|

||||

|

||||

Getting user input is achieved by calling Window.Read()

|

||||

|

||||

A typical call to Read:

|

||||

`event, values = sg.window.Read()`

|

||||

|

||||

`event` will be the event that happened. values are all of the window's widgets current values, in dictionary format.

|

||||

|

||||

Adding an event loop to the previous example results in this code:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

import PySimpleGUI as sg

|

||||

|

||||

layout = [[sg.Text('Filename', text_color='red')],

|

||||

[sg.Input(), sg.FileBrowse()],

|

||||

[sg.OK(), sg.Cancel()]]

|

||||

|

||||

window = sg.Window('Get filename example').Layout(layout)

|

||||

|

||||

# The Event Loop

|

||||

while True:

|

||||

event, values = window.Read()

|

||||

if event is None:

|

||||

break

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Within your event loop you take actions based on the event.

|

||||

Let's say you want to print whatever is in the input field when the user clicks the OK button. The changed event loop is:

|

||||

```python

|

||||

# The Event Loop

|

||||

while True:

|

||||

event, values = window.Read()

|

||||

if event is None:

|

||||

break

|

||||

if event == 'OK':

|

||||

print(values[0])

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

For buttons, when they are clicked, they return their text as the event, or you can set a "key" that will be what it returned to you when the button is clicked. Adding a key to our OK button is done by adding the `key` parameter to the `OK()` call.

|

||||

|

||||

`sg.OK(key='_OK BUTTON_')`

|

||||

|

||||

Now when the OK button is clicked, the event value will be `_OK BUTTON_`.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

# Widget Interaction

|

||||

|

||||

## Reading a widget

|

||||

|

||||

Any time that an event happens, you are provided a dictionary containing all of your widget's values.

|

||||

`event, values = window.Read() `

|

||||

|

||||

The`values` return code is a dictionary of the widget's values. Adding a `key` to the `Input` widget will cause that key to be what is used to "loop up" the value of that widget in the `values` variable.

|

||||

|

||||

If our `Input` widget was changed to have a key:

|

||||

`sg.Input(key='_INPUT_')`

|

||||

|

||||

Then the value for that input field can be obtained from the `values` variable. The value of the Input widget in this case will be:

|

||||

`values['_INPUT_']`

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## Changing a widget's value

|

||||

|

||||

Every widget has an `Update` method that will the widget's value or settings.

|

||||

|

||||

To update an widget, you must first get the object. You can either save it in a variable when you create it or you can look up a widget by it's key. Remember widgets are called Elements in PySimpleGUI. To get the Input Element in the previous example, you could call `Element` or `FindElement`.

|

||||

`window.Element(key)`

|

||||

|

||||

Once you have the element, then you can call the Update function:

|

||||

`window.Element(key).Update(value and settings)`

|

||||

|

||||

## Widget interaction

|

||||

|

||||

Building further on the `key` idea and Updating widgets, let's look at an example where the text 'Filename' is replaced by whatever you type in the input box.

|

||||

|

||||

The basic logic:

|

||||

If button == 'OK':

|

||||

change text to input field's value

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

import PySimpleGUI as sg

|

||||

|

||||

layout = [[sg.Text('Filename', text_color='red', key='_TEXT_')],

|

||||

[sg.Input(key='_INPUT_'), sg.FileBrowse()],

|

||||

[sg.OK(key='_OK BUTTON_'), sg.Cancel()]]

|

||||

|

||||

window = sg.Window('Get filename example').Layout(layout)

|

||||

|

||||

# The Event Loop

|

||||

while True:

|

||||

event, values = window.Read()

|

||||

if event is None:

|

||||

break

|

||||

if event == '_OK BUTTON_':

|

||||

window.Element('_TEXT_').Update(values['_INPUT_'])

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

As you can see, the pseudo-code on the real code look very similar.

|

||||

|

||||

Note the statement `if event is None` is what catches the user clicking the X to close the window. When the user does that, we want to exit the program by breaking from the event loop.

|

||||

|

||||

# Async Designs

|

||||

|

||||

Asynchronous designs are possible using PySimpleGUI. To use async, add a `timeout` parameter to the `window.Read()` call.,

|

||||

|

||||

## Example

|

||||

|

||||

Let's say you wanted to make a GUI that displays your latest emails, checking every 30 seconds. Rather than spin off a thread for the mail checker, run it within your GUI's event loop. Ideally we want the GUI to run as much as possible so that it's responsive. This is how it's accomplished

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

# The Event Loop

|

||||

while True:

|

||||

event, values = window.Read(timeout=30000)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

If you don't want to GUI to delay at all then set timeout=0. Setting timeout=0 will run in a completely non-blocked, async fashion.

|

||||

|

||||

# Wrap-up

|

||||

|

||||

The overall architecture was meant to enable someone to duplicate both the GUI at a near-pixel-level and the behavior of a program written directly in the tkinter or Qt framework. PySimpleGUI provides a way of interacting with the native widgets in a more Python-friendly, novice-user-friendly manner. It is not meant for large, commercial applications. Those types of applications are in the 20% not covered by PySimpleGUI.

|

||||

|

||||

### Portability

|

||||

|

||||

Both PySimpleGUI code and the PySimpleGUI package itself are highly portable. Taking a PySimpleGUI application from tkinter to Qt requires changing the import from `import PySimpleGUI` to `import PySimpleGUIQt`. That really is all that is typically required.

|

||||

|

||||

The PySimpleGUI module itself is highly portable too. Porting from tkinter to Qt took 1 week to get all of the widgets up and running with their basic operations.

|

||||

Loading…

Add table

Add a link

Reference in a new issue