I was frustrated by having to deal with the dos prompt when I had a powerful Windows machine right in front of me. Why is it SO difficult to do even the simplest of input/output to a window in Python??

With a simple GUI, it becomes practical to "associate" .py files with the python interpreter on Windows. Double click a py file and up pops a GUI window, a more pleasant experience than opening a dos Window and typing a command line.

Python itself doesn't have a simple GUI solution... nor did the *many* GUI packages I tried. Most tried to do TOO MUCH, making it impossible for users to get started quickly. Others were just plain broken, requiring multiple files or other packages that were missing.

The `PySimpleGUI` solution is focused on the ***developer***. How can the desired result be achieved in as little and as simple code as possible? This was the mantra used to create PySimpleGUI. How can it be done is a Python-like way?

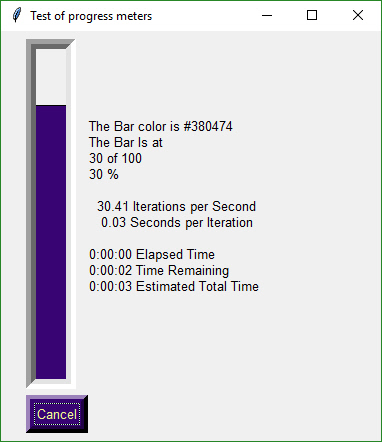

You can add a GUI to your command line with a single line of code. With 3 or 4 lines of code you can add a fully customized GUI. And for you Machine Learning folks out there, a **single line** progress meter call that you can drop into any loop to get a graphic like this one:

Simply download the file - PySimpleGUI.py and import it into your code

### Prerequisites

Python 3

tkinter

Should run on all Python platforms that have tkinter running on them. Has been thoroughly tested on Windows. While not tested elsewhere, should work on Linux, Mac, Pi, etc.

Yes, it's just that easy to have a window appear on the screen using Python. With PySimpleGUI, making a custom form appear isn't much more difficult. The goal is to get you running on your GUI within ***minutes***, not hours nor days.

The "High Level" API calls that *output* values take a variable number of arguments so that they match a "print" statement as much as possible. The idea is to make it simple for the programmer to output as many items as desired and in any format. The user need not convert the variables to be output into the strings. The PySimpleGUI functions do that for the user.

This feature of the Python language is utilized ***heavily*** as a method of customizing forms and part of forms. Rather than requiring the programmer to specify every possible option for a widget, instead only the options the caller wants to override are specified.

Here is the function definition for the MsgBox function. The details aren't important. What is important is seeing that there is a long list of potential tweaks that a caller can make. However, they don't have to be specified on each and every call.

The classic "input a value, print result" example.

Often command line programs simply take some value as input on the command line, do something with it and then display the results. Moving from the command line to a GUI is very simple.

This code prompts user to input a line of text and then displays that text in a messages box:

In addition to MsgBox, you'll find a several API calls that are shortcuts to common messages boxes. You can achieve similar results by calling MsgBox with the correct parameters.

Take a moment to look at that last one. It's such a simple API call and yet the result is awesome. Rather than seeing text scrolling past on your display, you can capture that text and present it in a scrolled interface. It's handy enough of an API call that it can also be called using the name `sprint` which is easier to remember than `ScrollectTextBox`. Your code could contain a line like:

sprint(f'My variables values include x={x}', f'y={y}')

This becomes a debug print of sorts that will route to a scrolled window.

There are 3 very basic user input high-level function calls. It's expected that for most applications, a custom input form will be created. If you need only 1 value, then perhaps one of these high level functions will work.

We all have loops in our code. 'Isn't it joyful waiting, watching a counter scrolling past in a text window? How about one line of code to get a progress meter, that contains statistics about your code?

With a little trickery you can provide a way to break out of your loop using the Progress Meter form. The cancel button results in a `False` return value from `EasyProgressMeter`. It normally returns `True`.

This is the FUN part of the programming of this GUI. In order to really get the most out of the API, you should be using an IDE that supports auto complete or will show you the definition of the function. This will make customizing go smoother.

It's both not enjoyable nor helpful to immediately jump into tweaking each and every little thing available to you. Let's start with a basic Browse for a file and do something with it.

It's important to use the "with" context manager. PySimpleGUI uses `tkinter`. `tkinter` is very picky about who releases objects and when. The `with` takes care of disposing of everything properly for you.

You will use this design pattern or code template for all of your "normal" (blocking) types of input forms. Copy it and modify it to suit your needs. This is the quickest way to get your code up and running with PySimpleGUI.

PySimpleGUI's goal with the API is to be easy on the programmer, and to function in a Python-like way. Since GUIs are visual, it was desirable for the SDK to visually match what's on the screen.

Forms are represented as Python lists. There are 2 lists in particular. One is a list of rows that form up a GUI screen. The other is a list of Elements (or Widgets) on each row. Each Elements is specified by names such as Text, Button, Checkbox, etc.

Some elements are shortcuts, again meant to make it easy on the programmer. Rather than writing a `Button`, with name = "Submit", etc, the caller can simply writes `Submit`. Some examples include: `Text` has a short-cut function named `T`. `TextInput` has `In`. See each API call for the shortcuts.

The next few rows of code lay out the rows of elements in the window to be displayed. The variable `form_rows` holds our entire GUI window. The first row of this form has a Text element. These simply display text on the form.

Now we're on the second row of the form. On this row there are 2 elements. The first is an `Input` field. It's a place the user can enter `strings`. The second element is a `File Browse Button`. A file or folder browse button will always fill in the text field to it's left unless otherwise specified. In this example, the File Browse Button will interact with the `InputText` field to its left.

The last line of the `form_rows` variable assignment contains a Submit and a Cancel Button. These are buttons that will cause a form to return its value to the caller.

This is the code that **displays** the form, collects the information and returns the data collected. In this example we have a button return code and only 1 input field.

This is a somewhat complex form with quite a bit of custom sizing to make things line up well. This is code you only have to write once. When looking at the code, remember that what you're seeing is a list of lists. Each row contains a list of Graphical Elements that are used to create the form.

The value for `button` will be the text that is displayed on the button element when it was created. If the user closed the form using something other than a button, then `button` will be `None`.

You can see in the MsgBox that the values returned are a list. Each input field in the form generates one item in the return values list. All input fields return a `string` except for Check Boxes and Radio Buttons. These return `bool`.

You will find it much easier to write code using PySimpleGUI if you use an IDE such as PyCharm. The features that show you documentation about the API call you are making will help you determine which settings you want to change, if any. In PyCharm, two commands are particularly helpful.

The most common use of PySimpleGUI is to display and collect information from the user. The most straightforward way to do this is using a "blocking" GUI call. Execution is "blocked" while waiting for the user to close the GUI form/dialog box.

You've already seen a number of examples above that use blocking forms. Anytime you see a context manager used (see the `with` statement) it's most likely a blocking form. You can examine the show calls to be sure. If the form is a non-blocking form, it must indicate that in the call to `form.show`.

Note several variables that deal with "size". Element sizes are measured in characters. A Text Element with a size of 20,1 has a size of 20 characters wide by 1 character tall.

Sizes can be set at the element level, or in this case, the size variables apply to all elements in the form. Setting `size=(20,1)` in the form creation call will set all elements in the form to that size.

In addition to `size` there is a `scale` option. `scale` will take the Element's size and scale it up or down depending on the scale value. `scale=(1,1)` doesn't change the Element's size. `scale=(2,1)` will set the Element's size to be twice as wide as the size setting.

The most basic element is the Text element. It simply displays text. Many of the 'options' that can be set for a Text element are shared by other elements. Size, Scale are a couple that you will see in every element.

Some commonly used elements have 'shorthand' versions of the functions to make the code more compact. The functions `T` and `Txt` are the same as calling `Text`.

**Fonts** in PySimpleGUI are always in this format:

A `True` value for `auto_size_text`, when placed on any Element, indicates that the width of the Element should be shrunk do the width of the text. This is particularly useful with `Buttons` as fixed-width buttons are somewhat crude looking. The default value is `False`. You will often see this setting on FlexForm definitions.

These make up the majority of the form definition. Optional variables at the Element level override the Form level values (e.g. `size` is specified in the Element). All input Elements create an entry in the list of return values. A Text Input Element creates a string in the list of items returned.

Buttons are the most important element of all! They cause the majority of the action to happen. After all, it's a button press that will get you out of a form, whether it but Submit or Cancel, one way or another a button is involved in all forms. The only exception is to this is when the user closes the window using the "X" in the upper corner which means no button was involved.

The Types of buttons include:

* Folder Browse

* File Browse

* Close Form

* Read Form

Close Form - Normal buttons like Submit, Cancel, Yes, No, etc, are "Close Form" buttons. They cause the input values to be read and then the form is closed, returning the values to the caller.

Folder Browse - When clicked a folder browse dialog box is opened. The results of the Folder Browse dialog box are written into one of the input fields of the form.

File Browse - Same as the Folder Browse except rather than choosing a folder, a single file is chosen.

Read Form - This is an async form button that will read a snapshot of all of the input fields, but does not close the form after it's clicked.

While it's possible to build forms using the Button Element directly, you should never need to do that. There are pre-made buttons and shortcuts that will make life much easier. The most basic Button element call to use is `SimpleButton`

The FileBrowse and FolderBrowse buttons both fill-in values into a text input field somewhere on the form. The location of the TextInput element is specified by the `Target` variable in the function call. The Target is specified using a grid system. The rows in your GUI are numbered starting with 0. The target can be specified as a hard coded grid item or it can be relative to the button.

The default value for `Target` is `(ThisRow, -1)`. ThisRow is a special value that tells the GUI to use the same row as the button. The Y-value of -1 means the field one value to the left of the button. For a File or Folder Browse button, the field that it fills are generally to the left of the button is most cases.

The `InputText` element is located at (1,0)... row 1, column 0. The `Browse` button is located at position (2,0). The Target for the button could be any of these values:

Target = (1,0)

Target = (-1,0)

The code for the entire form could be:

layout = [[SG.T('Source Folder')],

[SG.In()],

[SG.FolderBrowse(Target=(-1,0)), SG.OK()]]

**Custom Buttons**

If you want to define your own button, you will generally do this with the Button Element `SimpleButton`.

The `FileBrowse` button has an additional setting named `file_types`. This variable is used to filter the files shown in the file dialog box. The default value for this setting is

The ENTER key is an important part of data entry for forms. There's a long tradition of the enter key being used to quickly submit forms. PySimpleGUI implements this tying the ENTER key to the first button that closes or reads a form. If there are more than 1 button on a form, the FIRST button that is of type Close Form or Read Form is used. First is determined by scanning the form, top to bottom and left to right. Keep this in mind when designing forms.

The `ProgressBar` element is used to build custom Progress Bar forms. It is HIGHLY recommended that you use the functions that provide a complete progress meter solution for you. Progress Meters are not easy to work with because the forms have to be non-blocking and they are tricky to debug.

The "easiest" way to get progress meters into your code is to use the `EasyProgessMeter` API. This consists of a pair of functions, `EasyProgessMeter` and `EasyProgressMeterCancel`. You can easily cancel any progress meter by calling it with the current value = max value. This will mark the meter as expired and close the window.

You've already seen EasyProgressMeter calls presented earlier in this readme.

The final way of using a Progress Meter with PySimpleGUI is to build a custom form with a `ProgressBar` Element in the form. You will need to run your form as a non-blocking form. When you are ready to update your progress bar, you call the `UpdateBar` method for the `ProgressBar` element itself.

# ---===--- Loop taking in user input and printing it --- #

while True:

(button, value) = form.Read()

if button == 'SEND':

print(value)

else:

print('Exiting the form now')

break

#### Tabbed Forms

Tabbed forms are shown using the `ShowTabbedForm` call. The call has the format

results = ShowTabbedForm('Title for the form',

(form,layout,'Tab 1 label'),

(form2,layout2, 'Tab 2 label'))

Each of the tabs of the form is in fact a form. The same steps are taken to create the form as before. A `FlexForm` is created, then rows are filled with Elements, and finally the form is shown. When calling `ShowTabbedForm`, each form is passed in as a tuple. The tuple has the format: `(the form, the rows, a label shown on the tab)`

Use the example programs as a starting basis for your GUI. Copy, paste, modify and run! The demo files are:

`Demo DisplayHash1and256.py` - Demonstrates using High Level API calls to get a filename

`Demo DupliucateFileFinder.py` - Demonstrates High Level API to get a folder & Easy Progress Meter to show progress of the file scanning

`Demo Recipes.py` - Three sample forms including an asynchronous form

`Demo HowDoI.py` - An amazing little application. Acts as a front-end to HowDoI. This one program could forever change how you code. It does searches on Stack Overflow and returns the CODE found in the best answer for your query.

**Do not attempt** to call `PySimpleGUI` from multiple threads! It's `tkinter` based and `tkinter` has issues with multiple threads

**Progress Meters** - the visual graphic portion of the meter may be off. May return to the native tkinter progress meter solution in the future. Right now a "custom" progress meter is used. On the bright side, the statistics shown are extremely accurate and can tell you something about the performance of your code.

It's a recipe for success if done right. PySimpleGUI has completed the "Make it run" phase. It's far from "right" in many ways. These are being worked on. The module is particularly poor on hiding implementation details, naming conventions, PEP 8. It was a learning exercise that turned into a somewhat complete GUI solution for lightweight problems.